'The Little Mermaid' and pregnancy allegory

In celebration of Valentine's Day this year, my husband and I decided to watch a movie that had nothing at all to do with pregnancy: the 1984 romantic comedy Splash. Well, I should say that I decided. He merely told me that he'd never seen the movie, and I delightedly declared that we therefore needed to watch it immediately. But it really does have nothing to do with pregnancy... at least I thought it didn't when I suggested it.

The Little Mermaid (1837 Fairytale)

Hans Christian Andersen's fairytale centers an unnamed "little mermaid" who is described as both innocent and beautiful. When she turns fifteen, her family says to her, as Andersen writes, “Well, now, you are grown up" and allows her to venture on her own to the previously forbidden surface. Notably, the age of sexual consent in Denmark, Andersen's home country, has historically been fifteen years old, though most women did not marry in the mid-1800s until they were closer to eighteen. The little mermaid's "adulthood" thus does seem to denote a kind of sexual maturity.

When she reaches the surface, the mermaid sees a handsome prince on a sailing vessel and immediately becomes enamored with him, only to see him thrown overboard during a storm. She rushes to save him, pressing her body against his and kissing him once she gets him safely to shore. The story tells us that her physical contact with the prince means a great deal to her, but she is saddened that he doesn't know her or that she saved him:

"...she remembered that his head had rested on her bosom, and how heartily she had kissed him; but he knew nothing of all this, and could not even dream of her."

|

| Illustration from Fairy Tales of Andersen (Stratton) |

Not able to forget the prince or her dreams of being with him forever, the little mermaid seeks a way to become human. This brings her to a similarly unnamed sea witch, who tells her:

“I know what you want... It is very stupid of you, but you shall have your way, and it will bring you to sorrow, my pretty princess... for when once your shape has become like a human being, you can no more be a mermaid. You will never return through the water to your sisters, or to your father’s palace again."

Besides separating her from her former life forever, the mermaid must also endure two different kinds of sacrifice as a sort of payment for becoming human: she must give up "the most beautiful" part of herself in the form of her voice and she must also endure great physical pain. The witch explains that the mermaid's 'newly born' legs will be a kind of torture, one that she must go through to reach her goal of being with the prince and making a life together. Sure enough, when the mermaid stands on land, she feels "as if treading upon the points of needles or sharp knives; but she bore it willingly."

Because of this painful sacrifice, she is able to be with the prince, who takes her in and adores her, kissing her on the forehead constantly and marveling at the loyalty and devotion that she shows to him, even if she cannot speak. However, the prince does not love the mermaid in the way she loves him, and (more specifically) he cannot marry her. Instead, the prince is promised to another land's princess. In contrast to the mermaid, this princess is said to have been raised "in a religious house, where she was learning every royal virtue," and when the prince sees her for the first time she is noted as shining with "purity."

The little mermaid knows there is no place for her in the prince's life now that he's found the "pure" princess he will marry, but she has been physically changed forever by trying to be with him; she is now a human with legs and with no voice, no family, no support, and no home.

Not to be too literal with the metaphor, but one could easily draw parallels to an infatuated youth who becomes pregnant during this time; she finds herself unwed and alone with the possibility of having her whole life and body changed forever because of this pregnancy. The man of her dreams can choose not to be with her, can instead marry a virginal bride that his family has picked out for him, and himself be unchanged by any sexual or romantic connections before marriage; many young women throughout history, though, have not been not so lucky.

The fairytale then takes a turn that is drastically different from Disney's later adaptation; from the sea, the little mermaid's sisters call out to her and tell her that they have found a way she can return to her previous life: she must commit an act of violence against the prince. Indeed, an act of murder where the blood will fall "upon [her] feet" from a magic sea knife and cause her body to "grow together again, and form into a fish’s tail." Then she can return to the sea, live out her long life, and forget all about the prince.

The mermaid actually does decide to do this act, even going as far as to take the knife to the prince's bedroom; she is fully prepared to draw blood. However, she finds that she ultimately cannot do it, and so she instead decides to sacrifice her own life. She throws herself into some ocean waves, where she is sure she will die:

"She cast one more lingering, half-fainting glance at the prince, and then threw herself from the ship into the sea, [where she] thought her body was dissolving into foam. The sun rose above the waves, and his warm rays fell on the cold foam of the little mermaid, who did not feel as if she were dying."

The resolution of Anderson's story is an odd one. Instead of dying, the mermaid is magically transformed into a spirit who is charged with blessing children. If the mermaid-spirit can protect and bless children who are obedient and who do good deeds, she will eventually earn a place in heaven:

"For every... good child, who is the joy of his parents and deserves their love, our time of probation is shortened [and] we smile with joy at his good conduct."

However, if any spirit blesses and assists a naughty child, one who would make the world a worse place, they must "shed tears of sorrow, and for every tear a day is added to [their] time of trial!”

It's an... odd ending, to be sure. As a child, I was never quite sure what to do with this story's conclusion. Seeing it through the lens of a pregnancy metaphor, however, it strangely works. This original version of The Little Mermaid can certainly be viewed as a kind of allegory about teen pregnancy and unexpected single-parenthood. One may think of the magic knife in the story as a symbolic potential for ending a pregnancy, the choice to have an abortion. In this, the young woman's drawing of blood and sacrifice would allow her to return to her old life and not be physically changed any further by her dalliance with her rejected love. On the other hand, a choice not to terminate the pregnancy would mean a different sacrifice: the end of her old life and the beginning of a new existence where she must be a caretaker and watcher of children. As a mother now, she would likely feel joy at her child's accomplishments and tearful sadness for her child being "naughty" or showing cruelty, just like the spirits at the end of Andersen's fairytale.

The Little Mermaid (1989 Disney animated film)

Perhaps it is no wonder that Disney's G-rated animated movie took away much of the darkness of the fairytale and its ending. While much of the story plays out the same at the start of the adaptation, the mermaid, now given the name Ariel, is very mildly older (16 instead of 15), and her bodily sacrifice is not quite as gruesome as Andersen's tale. There is no mention of the physical pain she must go through for her to be with her prince, though her body is still permanently transformed and her voice still taken as payment for her desired change into a human by the sea witch Ursula.

The connection between Ariel's deal to become human and her sense of sexuality has been discussed by many critics over the years, with one analysis mentioning that Disney's The Little Mermaid can be read as being very much about both sex and reproduction. Ariel turning sixteen, just like in Andersen's story, is celebrated as symbolic of her reaching adulthood:

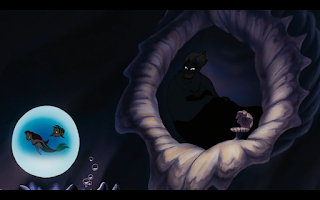

"Becoming an adult means you’re getting fertile and ready to mate. This Disney story is about what the right mate is and how to find it. The sexual is being displayed constantly throughout the motion picture... Ursula’s [cave] looks like the inside of a body, and she’s actually sitting in a giant vulva, including clitoris. [It's possible to] even see the crystal ball as an ovulating egg."

Ariel's transformation into a human can be seen as a parallel for her transformation into a sexual being.

However, ultimately the agency, choice, and growth in Disney's The Little Mermaid does not really belong to Ariel at all. While the story does feature Ariel growing up and becoming a reproductive being, the movie centers on more the choices and change of her father, King Triton. Ariel may have more physical changes in the story, but its her father who must make emotional changes and growth. Ariel is remarkably consistent in her goal to be with the prince and become a human, while her father must go through dynamic shifts in order for the film to reach its conclusion.

King Triton spends most of the film furious about his daughter's infatuation with the human world and her desire to transform into a land-dweller. He wants his youngest daughter with him, protected and chaste under the sea. Unlike Andersen's original mermaid protagonist, Ariel has no dramatic choice at all to make at the end of the the Disney film; there is no sacrifice or requirement of the mermaid's pain. Instead, whether or not Ariel will be with the prince is actually a choice made by her father, revealing that this film's arc is less about Ariel's own discovery of her sexuality and its consequences and more about her father accepting that his daughter is a grown woman now, one who is ready (arguably) to be a wife and mother on her own. The last lines of the movie, in fact, do not belong to the "little mermaid." Instead, it is a conversation between Sebastian the crab and the ocean king Triton. After Sebastian asserts the lesson that "children ought to be free to lead their own lives," Triton responds:

"Then I guess there’s only one problem left.

[And that is] how much I’m going to miss her."

With this declaration, Triton uses his magic to allow Ariel to transform into a human, smiling at her and silently communicating that she has his blessing to marry the prince. Ariel does not speak again in the film; her only act is to embrace the prince, kiss him, and (despite technically having her voice back) silently marry him.

Interestingly, Disney did create a sequel to The Little Mermaid, a direct-to-video story where Ariel is indeed shown post-pregnancy as a mother. She spends a whole song singing and holding her baby daughter, but it is notable that, by the end of the film, she also must ultimately learn the same lesson her father did about letting go; she must accept her daughter as her own person who will ultimately grow up, become her own autonomous and sexual being, and leave her.

Splash (1984)

Splash is the most overtly sexual of The Little Mermaid adaptations, as well as the one that strays the furthest from Andersen's story. There is no evil sea witch or horrible sacrifice to start the mermaid's journey to walking on land as a human. Instead, through ill-defined magic, the mermaid known later as Madison (Daryl Hannah) can appear to be human on land for about one week at a time during rare circumstances (not fully explained) involving the full moon. Like the Andersen story, she becomes enamored with a man she saves from drowning, but this time he is no "handsome prince" but instead a New York wholesale produce seller named Allen (Tom Hanks).

Unlike the subtle implications about sexual maturity in the other iterations of the tale, Madison's relationship with Allen is explicitly an adult and sexual one. Once she can walk on land, she presses her naked body to his and kisses him passionately, and she and Allen spend most of the movie all over each other, Allen at one point commenting that they'd had sex (or at least completed some kind of sexual acts) in "the car, and the elevator, and the bedroom, and on top of the refrigerator."

However, Madison does not have the consequence of changing her body permanently in order to have a physical relationship with Allen. This is a fling, a satisfying vacation that she plans to end without consequence. After six days, she will return to the sea and her old life, happy with her history with Allen but otherwise unchanged and unmarred.

However, as Allen falls harder for her, he frantically proposes, insisting that he's in love for the very first time.

After turning him down once and then staring at the sea questioningly for a night, Madison agrees to marry Allen. As the audience, we know what Allen does not: what Madison is giving up and leaving behind. Despite Allen's insistence that she can go back and visit home for the holidays and that she should only be excited by their rushed nuptials (Allen literally wants to drive out of state that night so they can elope immediately), the audience knows that Madison will be forever separated from her former life and forever bodily changed. This cluelessness can certainly parallel how little many men understand about the toll pregnancy can take on the body.

In the end, though, this outcome is not where the movie goes. As the film's page in TV Tropes notes, the ending of the movie is strangely complicated and progressive. After Madison is temporarily captured by scientists and held captive in a fish tank, Allen and some allies break her free, only to be cornered by the United States Army on a pier. ("I'm not entirely sure this movie knew how to end," my husband commented in response to this very 1980's chase scene.) This is where Madison offers Allen a reverse of the traditional The Little Mermaid choice: he can fall into the sea with her, allow himself to be changed forever and to never walk on land again. He would be separated from his business, his brother, and his community... but he would be with Madison and linked with her forever.

Allen agrees, and he follows her into the sea. The film closes with a happy montage of them swimming among tropical fish (which are somehow supposed to be in a New York harbor? The actual scenes were filmed in Bermuda, which makes more sense).

Despite the tone of the montage, TV Tropes points out how significant the sacrifice the film has Allen make. The movie establishes that it is Madison's presence that allows for Allen to survive under water, so he must stay with her forever. Also given some details from the movie, "Allen will [also] probably have to give up his human speech and instead learn to speak in high pitched dolphin squeaks" and ultimately will have to mourn "his loss of humanity."

The movie is unclear if Allen's body will change into that of a merman's, the way Madison's did in reverse on land, or if he can merely survive under the water with Madison's help. Either way, he potentially will experience "chronic sexual frustration," as the original sexual connection that he and Madison had relies fairly heavily on her human-appearing anatomy on land. He's given up his family, his friends, his home, his produce business, his own species, and even his ability to have sex with Madison in order to be with her, and thus he's also given up the power structure so prevalent in other The Little Mermaid adaptations. By the end of Splash, Madison maintains control over the form of her own body, and it is Allen whose body, sexuality, and life must adjust forever.

In this way, Splash is a modern fantasy, one where one's body, life, and sexuality can either be altered or not based purely on personal choice rather than gender. Created in a time when new forms of male hormonal birth control seemed potentially on the horizon (although the main candidate was soundly rejected by 1986 for unacceptable side effects), Madison and Allen's ending could allegorically be read as a fantastic future where men and women could be truly equal in terms of how love, sexuality, and family planning affect their respective careers, lives, and physical bodies.

Thus... perhaps it is fair to say that this cheesy movie from 1984 is even more of a fairytale than Anderson's original story.

|

| Illustration from Dover Classics, The Little Mermaid |

Comments

Post a Comment